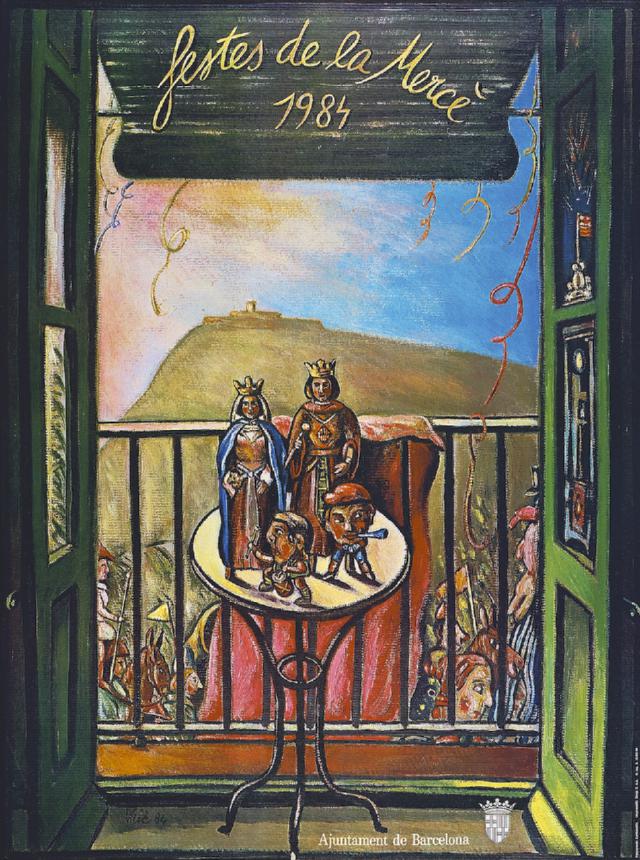

Alex Susanna

Amb motiu del seu setantacinquè aniversari, la Sala Parés acull una àmplia exposició retrospectiva de Miquel Vilà, un dels artistes catalans més singulars d'aquests darrers quaranta anys. Què entenem, però, per singular? Algú dotat d'una forta personalitat, algú que en tot moment ha propiciat un creixement òptim de la seva obra, i algú proveït d'una gran fe en el seu ofici. Personalitat, creixement, fe. Però potser per damunt de tot Miquel Vilà ha estat algú capaç de crear un imaginari propi, i llavors ja estem parlant de talent.

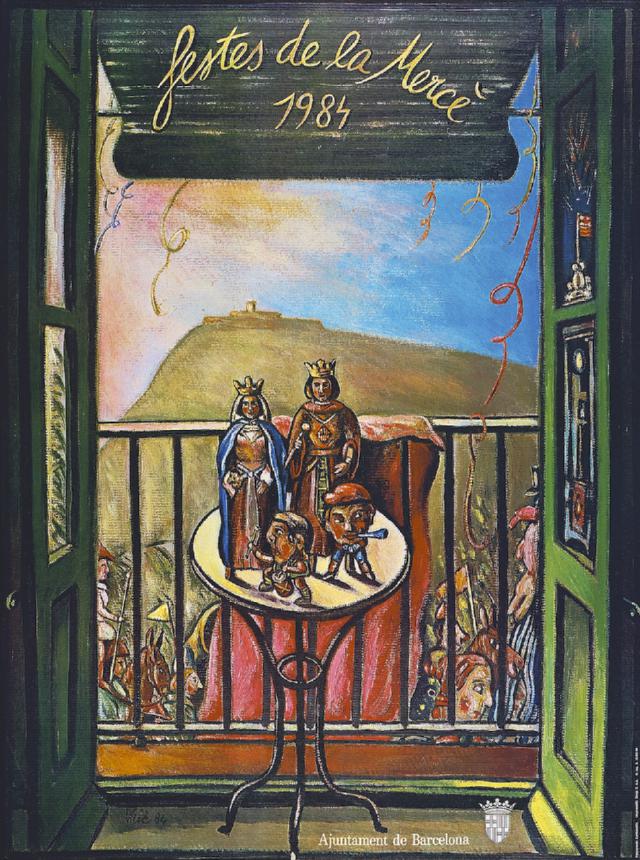

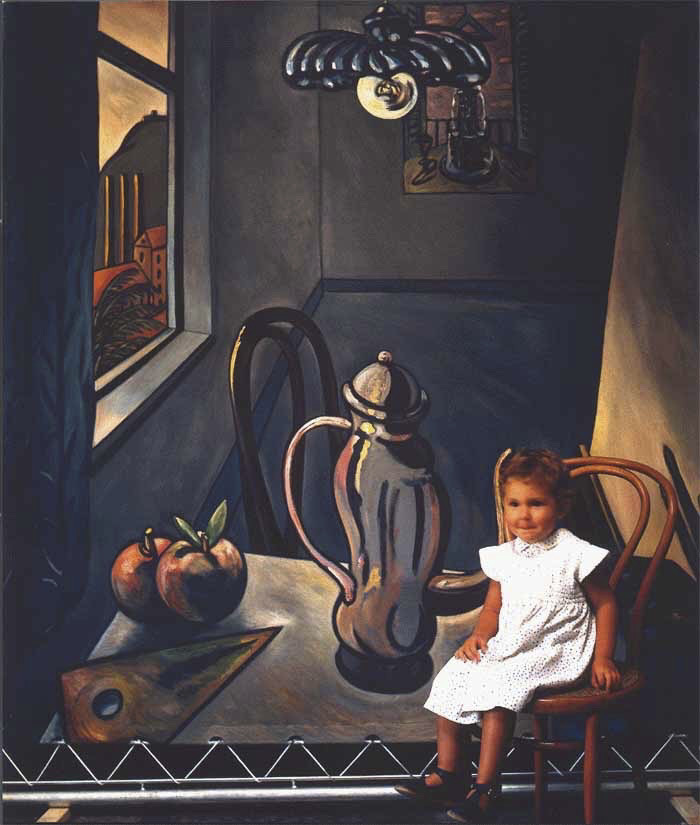

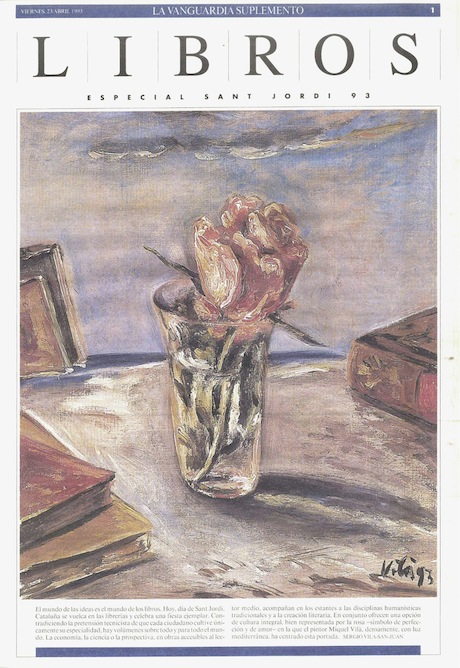

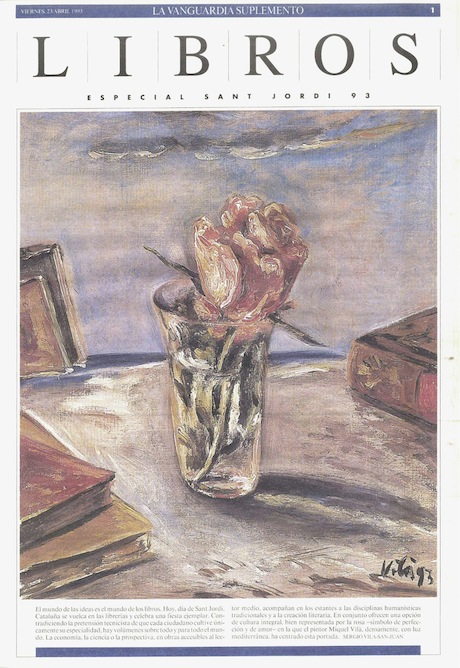

D'un talent insubornable i perseverant, com ens ho demostra l'exposició que presentem, i que recull de manera sintètica una trajectòria de gairebé mig segle: des d'algunes d'aquelles primeres obres -entre surreals i deutores del pop-art- que va exposar el 1968 a les galeries Ianua (Barcelona) o Pecanins (Mèxic), o el 1969 a L'Agrifoglio (Milà) i a The Mande Kerns Center (Eugene, Oregon), fins a tot de quadres pintats aquests darrers anys al seu estudi de Barcelona o de Maó, en què la seva obra sembla haver assolit un grau de condensació extrema. Bodegons mínims, paisatges sense anècdota: pura plàstica.

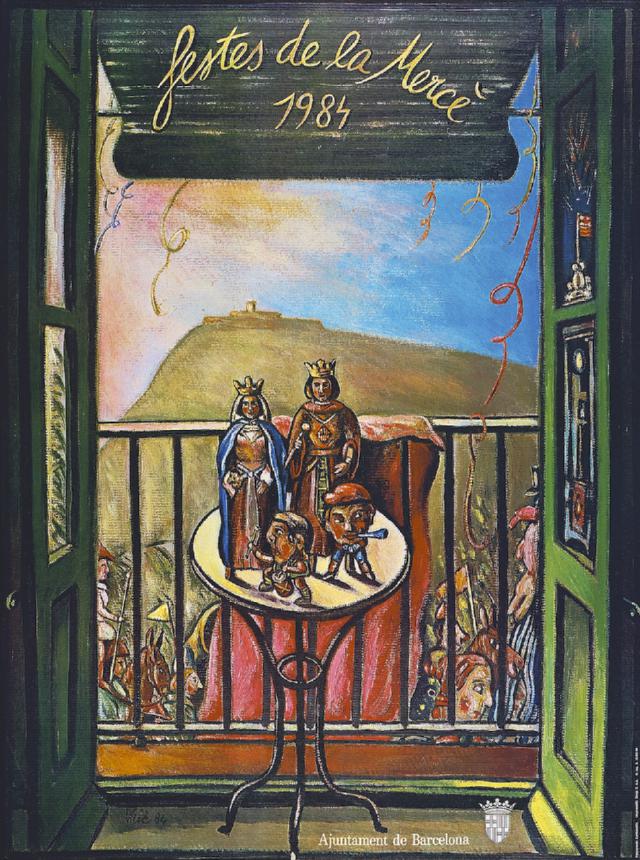

És doncs una exposició que tant l'artista com la Sala Parés -la seva galeria des de 1990- ens devien, i el primer que hem de fer és celebrar-ho com cal. No és encara la gran retrospectiva que es mereix Miquel Vilà, però potser en sigui el preàmbul. I, en qualsevol cas, la tria d'aquesta seixantena d'obres funciona no sols com un autèntic compendi de motius i gèneres sinó com una excel.lent porta d'entrada al seu món. Si ho voleu, és un format d'exposició poc freqüent -com l'equivalent d'una antologia poètica-, però molt útil i suggerent per acostar l'obra dels nostres clàssics moderns a les noves generacions i donar-nos als altres l'oportunitat de fer un viatge exprés per tota la seva trajectòria.

L'obra de Miquel Vilà és, en aparença, la d'un outsider, la d'algú que sembla haver-se mogut pels marges dels corrents principals de l'art del nostre temps. Però ben mirat no és ni de lluny allò que sembla: si hi ha un pintor culte, viatjat i llegit, és ell. Un pintor, a més, dotat d'un elevat grau d'autoconsciència. La gràcia de tot plegat és que això l'ha fet summament independent: com sol passar en aquests casos, ell ha triat els seus predecessors -les afinitats que per alguna cosa es diuen electives- i no ha deixat de dialogar-hi mai. En lloc de les vies francesa o nordamericana molt més fressades, ell ha preferit transitar sobretot per la italiana i és doncs amb alguns dels principals pintors del Novecento que més ha conversat des de mitjan dels anys setanta, quan la seva obra troba el seu propi to: Carrà, Sironi o De Pisis, per esmentar-ne uns quants, però no els únics.

Per tant, contra el que pugui semblar, l'obra de Vilà no l'hem pas de veure com l'expressió més o menys malenconiosa d'un soliloqui sinó tot el contrari. Si abans parlàvem d'alguns pintors italians, ara toca afegir-hi els seus companys de generació: Josep Vives Campomar, Xavier Serra de Rivera i Francesc Artigau són potser aquells amb qui ha mantingut una relació més fèrtil, la qual cosa cosa sovint s'ha traduït en exposicions conjuntes. Tots ells formen part de l'anomenada generació dels 60, una de les més invisibles als nostres museus públics (tot sigui dit de passada).

Sigui com vulgui, els seus quadres els reconeixeu -gairebé sempre-de seguida: sol haver-hi una "amosfera Vila", com va dir Francesc Fontbona al pròleg del Catàleg raonat (2004) del nostre artista, que emergeix en cada obra i acaba per configurar un món. Un món de referències tant externes com internes: aparentment hi trobem uns mateixos motius o pre-textos, però tant o més que la seva materialitat visible i reconeixible ens importa el punt de vista des del qual són observats, o, més ben dit, presentats.

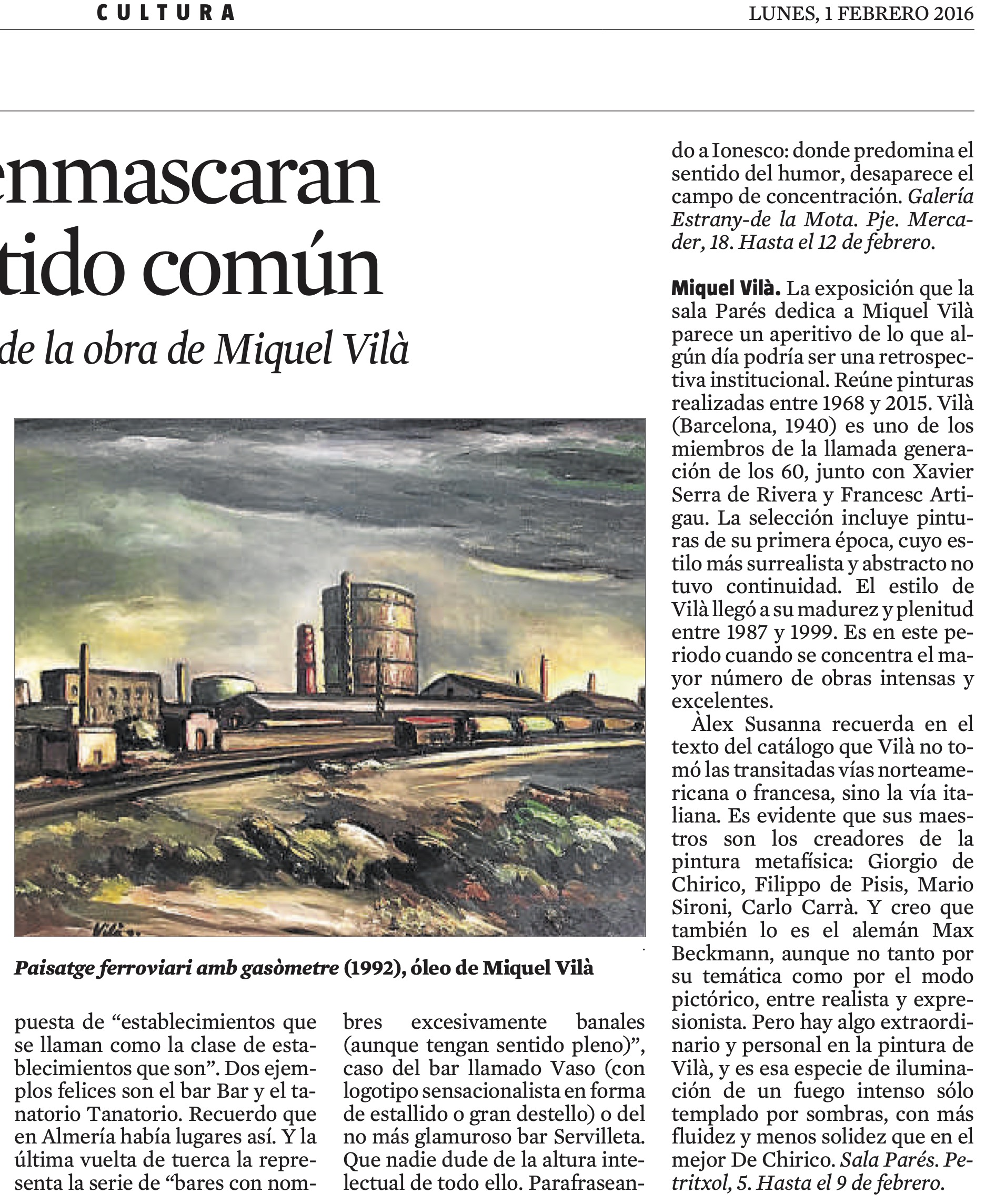

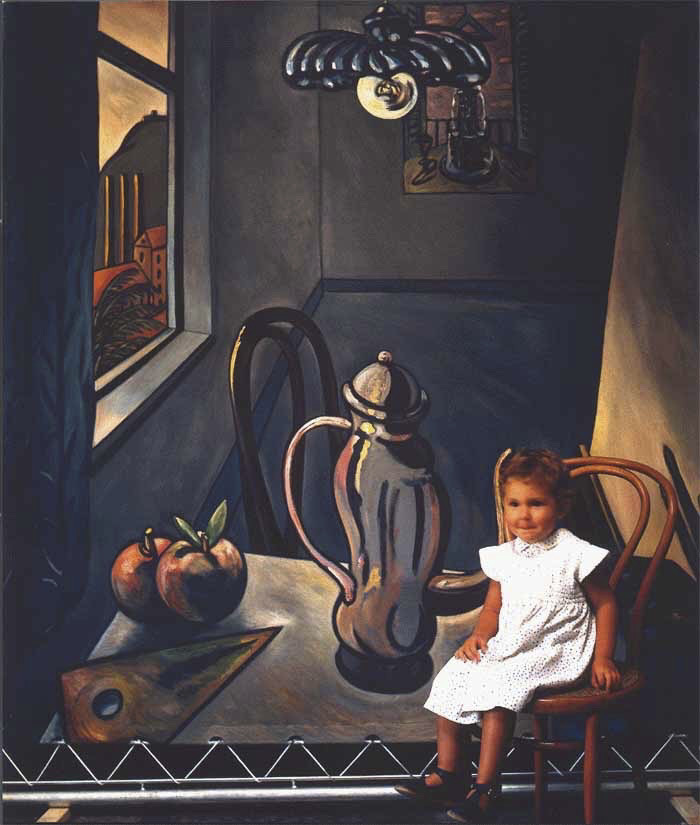

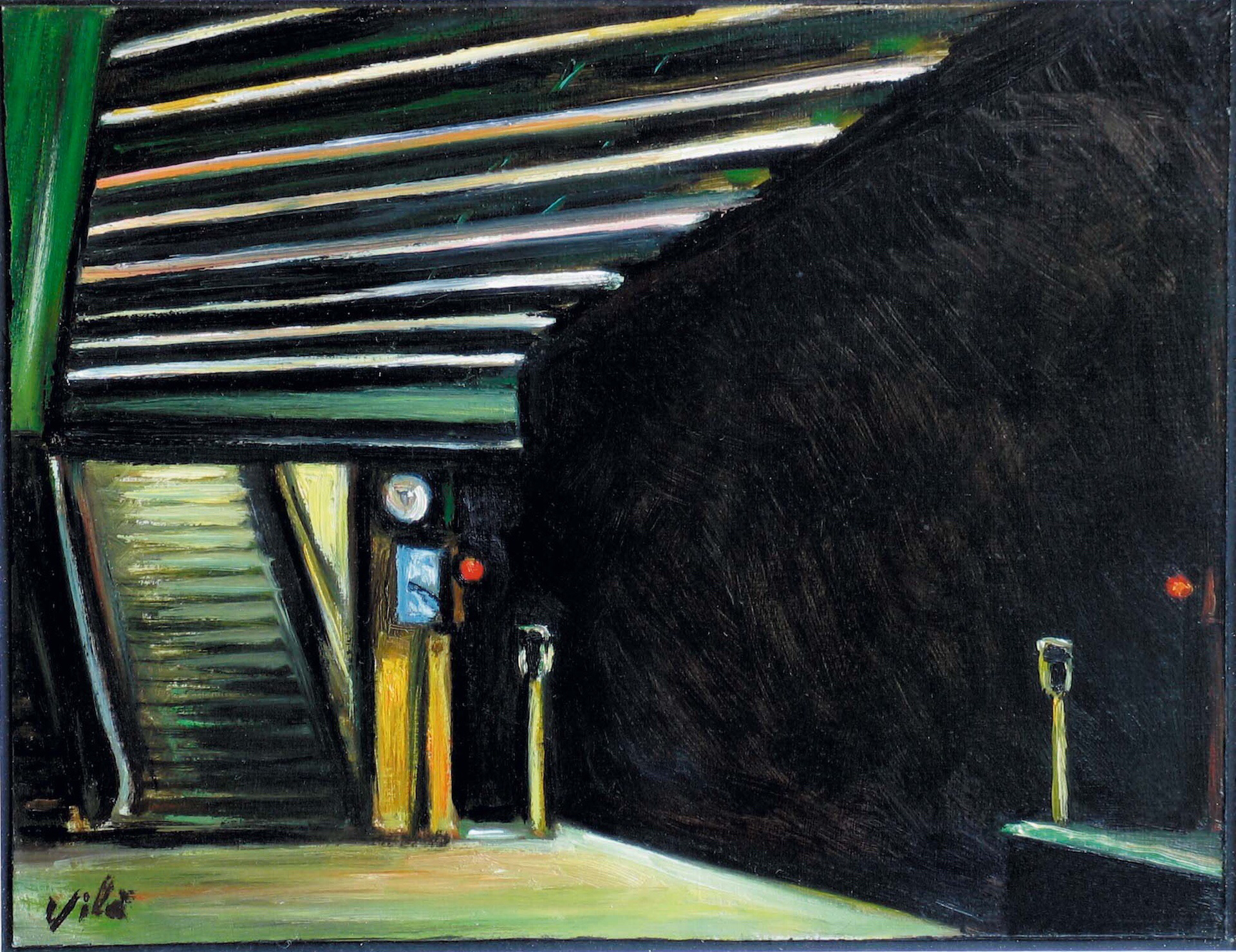

Una perspectiva sempre d'allò més subjectiva i fecunda, sovint torbadora i tot: la fisicitat dels seus paisatges -industrials o naturals-sol cristal.litzar en un món d'una certa irrealitat, de la mateixa manera que els objectes que habiten els seus bodegons estan gairebé sempre en fora de joc -fora de lloc-, però per això mateix creen uns camps magnètics del tot inesperats. La subversió del real, vet aquí el lema que presideix implícitament gran part de la seva obra.

Ara bé, d'on li ve aquesta llum que algú no va dubtar a emparentar amb la de Nonell? Una llum dramàtica, de capvespre tardoral. Una llum interior, untuosa, oliosa, que sembla regalimar per la pell dels objectes, o dels mateixos paisatges. Una llum fluorescent, com de final de cicle. Que subratlla, sotto voce, la soledat de les coses i l'allunyament respecte dels paisatges que ens envolten, tant els industrials -ja desapareguts- com els naturals, als quals cada cop té més tirada. Una llum que probablement és la màxima conquesta de l'artista i alhora un senyal de la seva inequívoca soledat. I és que, com va dir Jordi Gabarró, "Miquel Vilà simbolitza perfectament aquesta lluita dels grans pintors actuals contra la mort de la pintura".

Alex SUSANNA

Maria Aurelia Campmany

La realitat és atractiva, així ho descobriren els fills del silenci. Podem anomenar els fills del silenci als que van néixer a la post guerra. Miquel Vilà neix al 1940 i obre els ulls a la quietud, en el miasma de la pau. Tot allò que es fa o que es diu a l'entorn d'aquests xicots que creixen ens els anys de la post guerra està encoixinat de silenci. Ningú no parla de res, o bé si diu alguna cosa ho fa amb cautes al.lusions, o més bé encara, menteix. L'art de la Barcelona estraperlista de la post guerra menteix. Marines i bodegons a metres. Retrats de la Sra. d'en Pau, d'en Pere o d'en Berenguera...retrats de la Sra...així fins a l'infinit. Com a conseqüència de tanta realitat mentidera es produeix la fuga de la realitat. I els nascuts en els anys 40 contemplen atònits com tot es dissol, tot o quasi tot.

Per totes aquestes raons i moltes més, Miquel Vilà descobriria que la realitat és atractiva, i descobriria més, a saber que això que anomenem realitat és el resultat de la nostra interpretació del món. Cert que els homes del Renaixement descobrien la Naturalesa i que el món estava escrit en caràcters matemàtics. Cert que decidien que el món era immediat, no transcendent i en conseqüència es disposaven a pintar, no allò que creien, sinó allò que veien. Però també és cert que allò que veien, l'ordenació sàvia de les dades que subministraven els sentits, era el producte de la seva concepció de l'Univers. Dit això, grosso modo: l'Adam de Miquel Àngel no és menys inventat que el Pantocràtor, és un pantocràtor.

La realitat és doncs allò que es busca i es troba al final d'un llarg procés d'el.lecció. Per això l'art és un art, és a dir, una virtut, una feina reiterada.

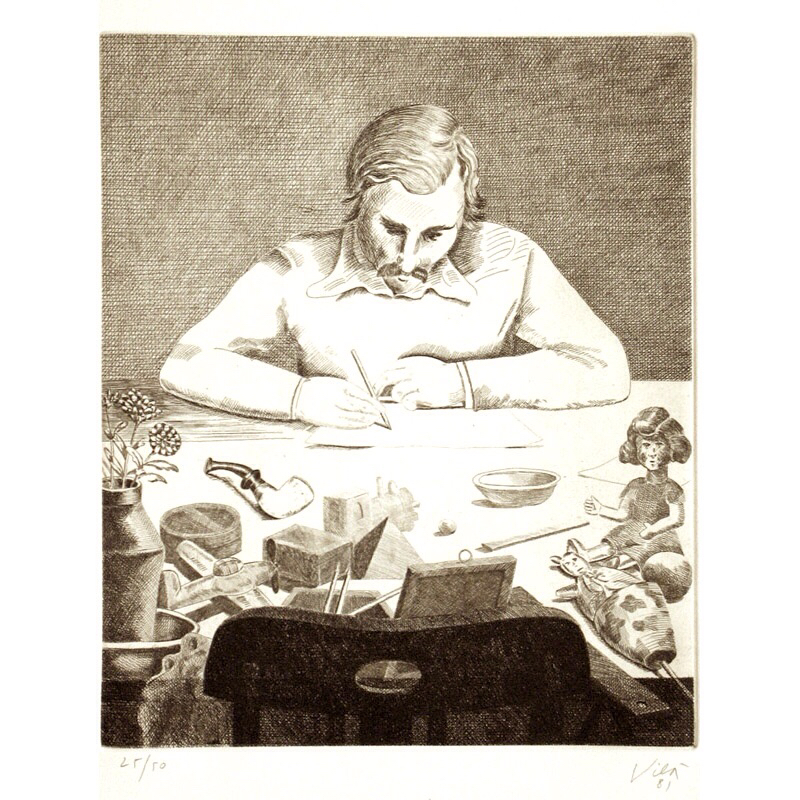

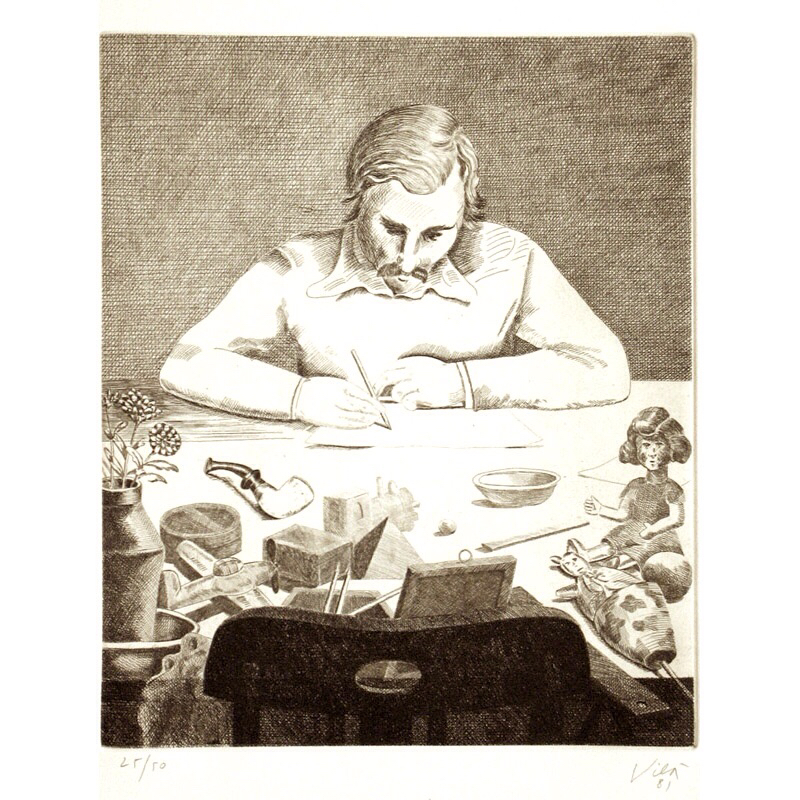

Per això és tan profundament i còmodament significatiu que en Miquel Vilà comenci la seva aventura creacional en un taller. L'impressor, el gravador gravitaran en el fons de la seva trajectòria de pintor. Aprendrà molt aviat que el llenguatge pictòric és un conjunt de signes, amb unes lleis de periodicitat, de paral.lelisme, de convergència, exactament igual que el llenguatge oral. Aprendrà a desconfiar de l'orgia romàntica, aprendrà que la llibertat no neix de la incoherència sino del rigor.

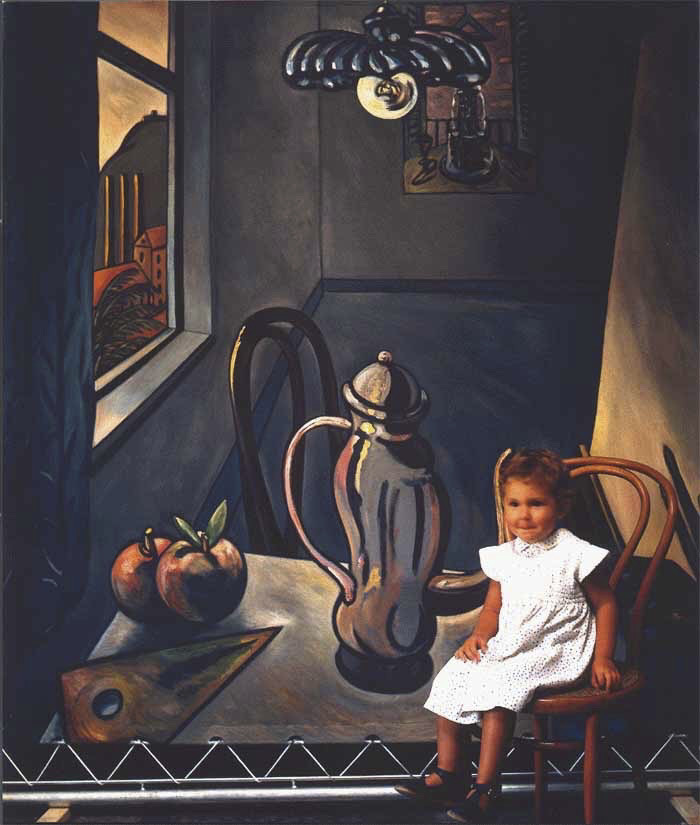

A poc a poc, Miquel Vilà ingressa a la pintura, i diries que hi ingressa descobrint que la realitat no és mai reproduïda, sinó produïda. I així van sortint del llenç les estances buides i els paisatges emmarcats. Els espais buits es van omplint de sol ponent i de terra càlida, són llocs on no hi ha ningú, són cantonades, racons, cases solitàries on, deliberadament, no hi ha ningú. Hi ha un clima d'espera i d'abandó, que ara, a poc a poc, en les últimes obres de Miquel Vilà s'il.lumina amb una claror d'una exhuberància inquietant. I t'adones que en Miquel Vilà no s'ha deixat endur per l'esperonament de la novetat a ultrança, ens exposa, simplement el que ha descobert, i és com podeu veure, absolutament inèdit.

Maria Aurelia Campmany

Francesc Miralles

Miquel Vilà és un pintor expressiu i personal, actual i intemporal, modern i antic, aliè a les modes artístiques i emparentat amb una tradició figurativa, ja d'aquest segle que representen les marines com objectes de Filippo de Pisis, els paisatges industrials de Mario Sironi, les arquitectures solitàries de De Chirico i fins i tot les reunions d'objectes íntims de Ramón Gaya. El que dòna caràcter a la seva pintura és, sobretot, l'ús del color i de la il.luminació. Hi ha un Miquel Vilà líric pels seus colors encesos i un altre de dramàtic pels seus colors apagats i ombrívols. En aquest sentit, la seva pintura ve a ser una síntesi dels esmentats De Pisis i Sironi, una síntesi que es manifesta com una tensió perpètua entre el gris i el fogós, el neutre i l'íntim, el fosc i el vivaç.

Francesc Miralles

Rafael Santos Torroella

He seguit de prop la carrera d'en Miquel Vilà des del seu començament quan estava entregat al que semblava la seva vocació més immediata: les tècniques del gravat. En aquell temps, quan encara estava associat amb en Torralba, un altre gravador, fins i tot vaig arribar a col.laborar amb algun dels primorosos llibres que varen editar. Tímidament, amb aquest tarannà silenciós que el caracteritza, es va donar també a conèixer per el que més l'hi deuria anar per dins, la pintura, quan ja ho estaven fent de pressa i corrent altres pintors pertanyents a la que s'ha anomenat la generació dels 60: un Artigau, un Arranz Bravo, un Bartolozzi, un Robert Llimòs, un Gerard Sala, un Serra de Rivera... Amb el darrer, tanmateix notable gravador, compartiria una certa inclinació amb René Magritte, un rodeig necessari potser per un i altre per el que em sembla que pressentien com la meta més desitjada possible: un realisme sense ambages, que fós tan vertader en la seva presència natural com, a la vegada, en quan a recreació o resposta pròpia des de la pintura a ella mateixa.

Després em va semblar veure'l avançant en solitari, amb lentitud i tenacitat,de vegades amb dificultats però sentint-se, en la seva obstinació, cada cop més justificat interiorment per l'empeny que l'impulsava. Cada cop que l'he tornat a veure, sovint després de molt temps, m'ha sorprès descobrir en la seva pintura quelcom de nou, en el sentit de diferent, veient-lo més proper a aquella meta, sigui quina sigui, més pressentida que dibuixada davant d'ell.

Des de fa uns anys però, aproximadament des de mitjans del vuitanta, vaig començar a advertir en les seves obres un inequívoc i com sobtat fulgor que, en algun moment em sortia al pas fent-me replantejar de nou la pregunta que més d'una vegada m'havia fet: ¿com és possible que per mi, el pintor més profund que ha tingut Catalunya, Isidre Nonell, hagi quedat allà, parat en el temps com a lluentor entre les ombres, el fulgurant rastre de les seves petjades?

Sé que avui em puc fer aquesta pregunta a propòsit precisament de la pintura de Miquel Vilà perquè no és una impertinència ni una gratuïtat que pugui entorpir ni una mica el seu segur camí. A més a més, no es tracta d'assignar-li qualsevol mimètica literària. Cadascú escolleix o troba per si sol als seus millors amics i, entre els que Goethe anomenava les nostres "afinitats sel.lectives" estic segur que Vilà hi inclou a Nonell, entre moltes altres. Per exemple, jo l'he sentit parlar amb entusiasme de Corot i ho puc entendre molt bé, justament i per estrany que sembli, a partir de les seves afinitats nonellianes; està clar però que en aquest darrer cas es pot tractar d'una cosa més particular i íntima, com emanada del seu propi entorn personal.

Per parlar de Nonell se'm fa imprescindible fer-ho a partir de Francesc Pujols a qui devem les més vives i sucoses impressions sobre ell. Com quan ens diu que el que aquell va fer va ser anar de dret a la substància d'allò bell, que en l'irrepetible pensador de La Torre de les Hores era sinònim de la Vida en la plenitud de la seva saó, "oblidant-se de tot el que constitueix el classicisme perquè de la quantitat més petita possible d'aquest se'n pugui obtenir la quantitat primordial més gran, també possible, de la seva substància i fer que l'obra d'art es converteixi en essència pura, com si exprimíssim una i altra vegada la Bellesa per treure'n tot el seu suc.

Davant les obres de les tres darreres campanyes menorquines de Miquel Vilà se'm han tornat a associar els noms de Pujols i Nonell al observar com en ells apareix també això que tan gràficament ens descriu el primer com quelcom de paladejat amb creixent intensitat en els quadres del segon. I això tan en el posat i l'absort recolliment en sí mateixes de les seves gitanes, com en aquells bodegons que són essència pictòrica medul.lar pura, en el sentit que Pujols fa servir la paraula. Així, de seguida notem que en els colors d'en Miquel Vilà hi passa alguna cosa. Són molts colors, molt enters. No tant però pel matís de les seves tintes o pigments sinó per aquesta substància de la qual ens parla el filòsof de Martorell. Els colors doncs, són substancials, substantius, que existeixen de per sí, més cap a dins que a fora. No se'ns queden a la superfície d'ells mateixos que és el que els passa a aquests pintors als quals es qualifica de "coloristes". I si a algú li pogués estranyar la densitat del color del nostre pintor, ell li podria dir com ho va fer el vell Rembrandt a un client que posava objeccions d' aquest tipus a una de les seves darreres obres: "Perdoni senyor però jo sóc un pintor, no un tintorer".

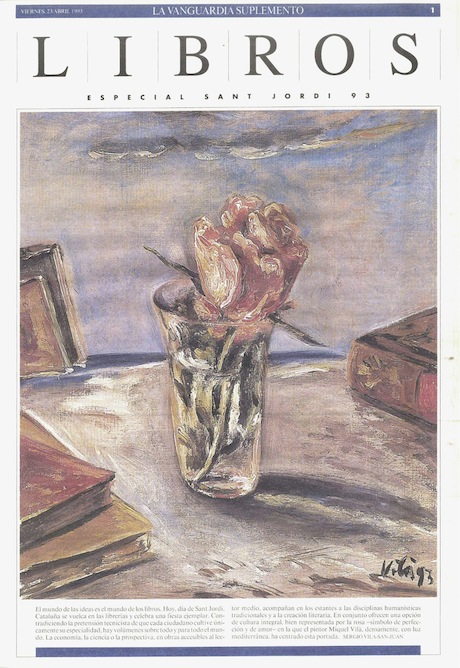

D'aquí és d'on ve la corporeitat de les coses de Miquel Vilà. Més que de les formes en sí mateixes prové del pes específic dels colors. D'una manera similar es pot notar el mateix en la carnositat càlida de les seves flors i llegums. També en la tersa closca d'un cranc o en una arengada. L'òxid de cadmi i l'ocre entre els verds i blaus metàl.lics tan propers als de Nonell. Fins i tot en una petita marina "El dic flotant, Barcelona". Es pot veure en aquesta darrera pintura com aquesta substantivitat que he esmentat abans arriba a la mateixa aigua, donant-li un batec, una mena d'animació interna que es confon amb la seva paradoxal detinguda imminència d'onada movent-se cap a la platja.

En general, en els bodegons d' en Vilà les coses tendeixen com en les de Nonell a anar pel seu compte. Això és contradictori a la tendència d' amuntegar, tan característica de l'utilitarisme humà.

D'aquesta forma, les coses es converteixen en protagonistes fins i tot vers elles mateixes la qual cosa els confereix eventualment un significat més profund. Això vol dir que en M. Vilà els hi afegeix una mica de sublimitud però a la vegada de patiment: ja no quedaran resignades a aquesta passivitat, a aquesta fixació o immobilitzada serenitat agònica que és l' última extremitud de la vida. Aïllades però no "aturades", estan encara en actiu, recorregudes per subtils tensions que es dirien íntimes, com en tot ésser viu. La composició que s' anomena "Safata i cadira en un interior" és potser la més aconseguida entre les darreres obres que conec d' en Miquel Vilà. En aquest quadre l' enunciat es fa com el dels protagonistes dins d' una escenografia, on cadascú estigués representant el paper que com a actors els correspon.

Si s' afegeix a tot això la funció que desenvolupa l'espai en el nostre pintor, el mateix en el seus interiors que en els seus paisatges, s'obtindrà un element més, molt significatiu, de la sorprenent animació, a vegades amb un punt de larvat dramatisme, que caracteritza les seves obres més recents. En aquestes, l'espai sol estar circumscrit per uns plans que no són els de la horitzontalitat i la verticalitat habituals, sinó que impliquen alguna cosa diferent: com una mena d'ansietat inexplicable, tanmateix en estat d' imminència cap a un misteri davant de les portes del qual se'ns abandona, més captivats que indecisos. No és estrany que el terra, -aquí també una mica a la manera de Nonell-, assumeixi en aquestes obres del darrer Vilà una importància ambiental més gran que la propia atmosfera i l'aire. En certa manera és com si conspirés, no contra ells sinó amb els, encara que per encaminar-los millor cap a aquesta repetida substantivitat que, com molt bé varen saber els antics primitius dels quals tant han après des de Cèzanne els primitius moderns, l' aire i l'atmosfera a poc que se'ls deixi sempre estaran disposats a robar-li.

Rafael Santos Torroella

Francesc Fontbona

Cada dia sóc menys partidari de classificar l'obra d'un artista dins d'una o altra tendència preestablerta. I menys encara quan l'artista està en plena corba ascendent de creació, i, per tant, no ha acabat el seu cicle creatiu. L'important és, en aquests casos, que l'artista faci una obra capaç de despertar sentiments, inquietuds o plaers a aquell qui la mira, i no pas a quin "isme" pertany.

No parlaré doncs, per això, de la pintura de Miquel Vilà, perquè si hi ha algú que encara no la coneix, ara la pot tenir a la vista, i arribar tot sol a les millors conclusions que en matèria d'art sempre són les que un mateix genera, sense haver de fer servir caminadors. Els adults no en necessiten de caminadors. A ningú se li ha de dir què li ha d'agradar o interessar. A part que a la pintura viva, la que encara no s'ha instal.lat en una categoria històrica, com a art visual que és, les paraules li fan més aviat nosa.

Només diré que l'obra de Miquel Vilà ja és una mica la d'un clàssic -el jove artista, tot i que no ho sembla, ja té mig segle-, un clàssic modern, amb una rica trajectòria al darrera seu, que mai ha deixat de tenir esma per anar evolucionant dins del seu personal camí. I els clàssics, com és lògic, no cal presentar-los; el que cal és mirar-se'ls.

El que sí voldria esmentar són alguns trets de la personalitat humana de Miquel Vilà, perquè aquesta difícilment serà coneguda per l'espectador que s'acosti a la seva exposició.

Home aparentment tímid, sorprèn per la seguretat que demostra en expressar els seus criteris, amb els que hom podrà estar-hi o no d'acord - jo haig de reconèixer que habitualment n'estic -, però que són sòlidament fonamentats. Els seus són criteris que naturalment, tampoc es basen en l'acció de caminadors, i que fins i tot dits en públic desentonaríen en l'orfeònic context dels axiomes artístics d'avui. Miquel Vilà neda contra corrent, i no solament ho sap sinó que n'està orgullós. I aquest nedar contra corrent s'evidencia també en la seva pintura, que mai ha tingut res a veure amb cap moda i que resulta estranya no només als ulls dels avantguardistes oficials sinó també als dels dipositaris de les essències tradicionals

Miquel Vilà, un solitari malgrat haver-se sentit solidari de certs companys de generació -entre ells Vives Campomar, l'altre expositor d'avui-, no juga el joc de les modes intel.lectuals, tan frívoles com les modes decoratives de temporada, ni és candidat a crear-se un panteó en vida. Per això té garantida la indiferència de tots aquells que només es preocupin d'allò que cal fer, sense que ni ells ni ningú sàpiguen qui decideix aquest caldre. Però jo vull creure, tot i no estar tan segur de la meva creença com Vilà ho està del seu camí, que en canvi té garantit també el respecte i l'admiració d'aquells altres que avui i sempre sabran valorar la força de la independència i de l'autenticitat.

Francesc Fontbona

Gemma Romagosa

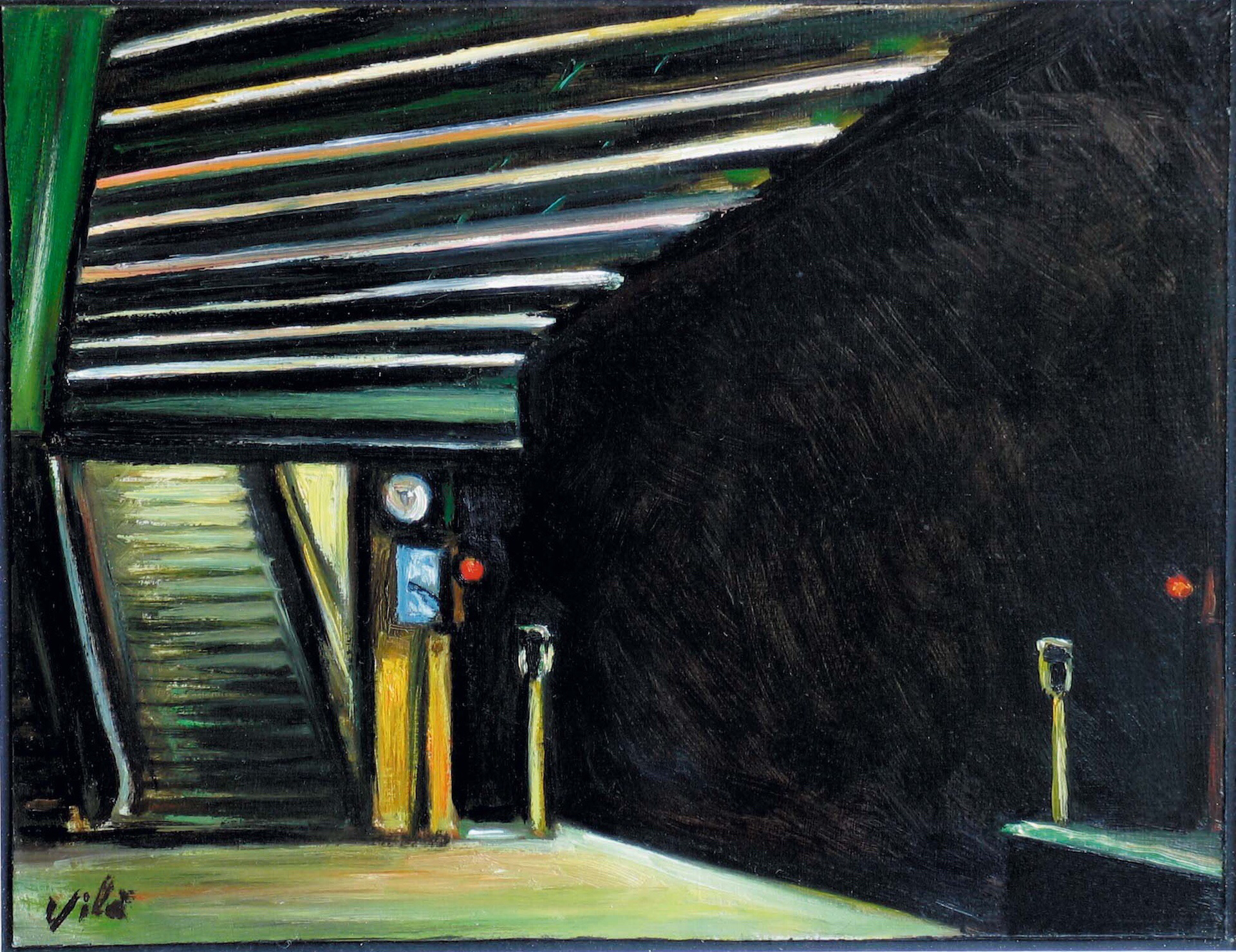

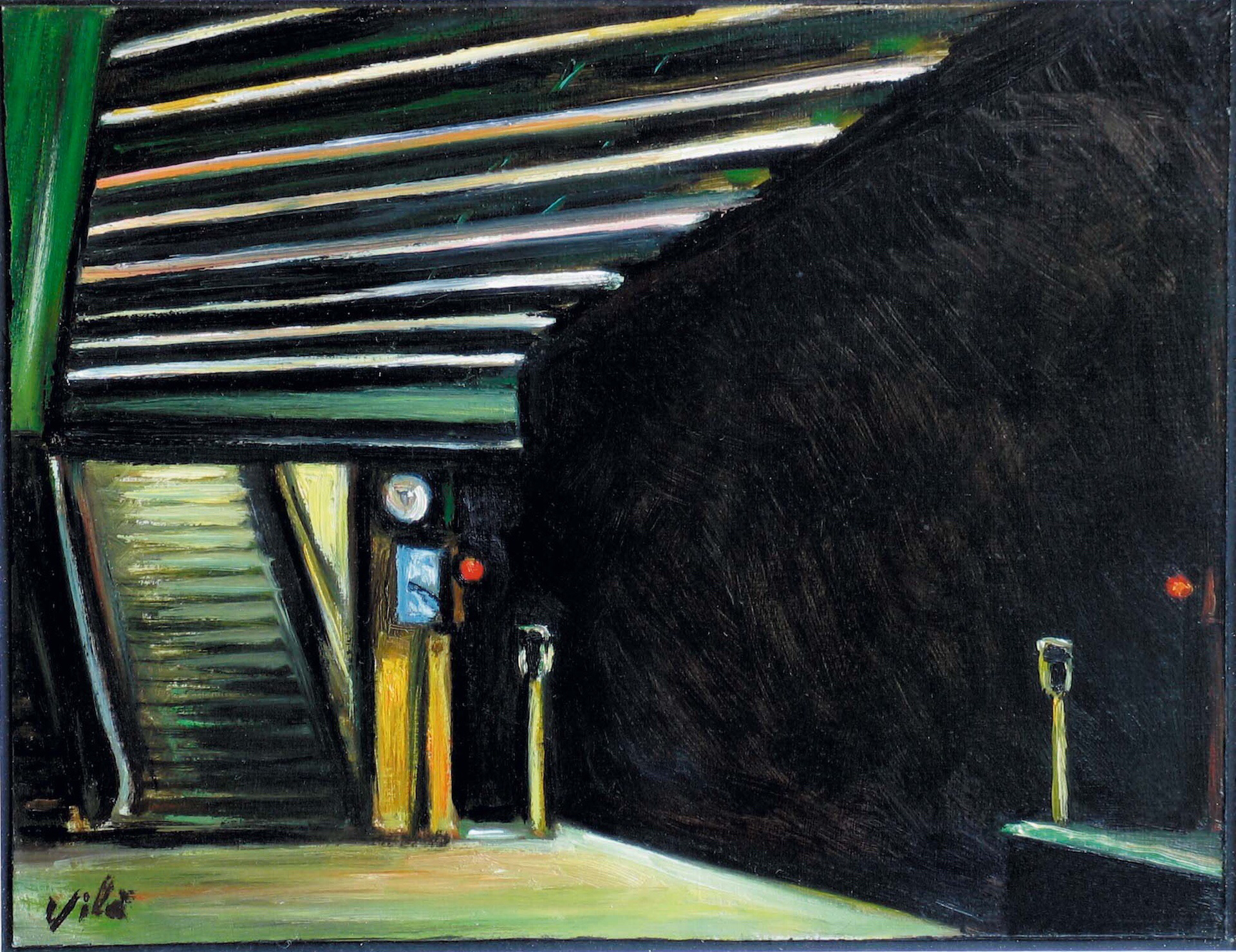

Res no sembla torbar la calma que regna en els paisatges de Miquel Vilà. Els edificis s'aixequen com a protagonistes d'un món desolat. Són escenaris en teoria coneguts, i dic en teoria perquè no hi ha indicis, malgrat l'exquisit realisme del pintor , que vulgui situar-nos en lloc. Al contrari, la realitat en l'obra de Miquel Vilà està vista d'una manera "irreal". Allò que coneixem pot esdevenir desconegut per obra d'una pertorbadora absència de personatges i també a causa del clima, de l'ambient indeterminat que es crea en desvetllar misterioses complicitats entre la llum i l'ombra.

Gemma Romagosa

Félix de Azúa

Durante un siglo, entre 1870 y 1970, la pintura tomó el relevo de la música en el progresivo desarrollo de las artes hacia su clarificación y autonomía, de manera que la obra individual se mantuvo bajo la tutela de lo colectivo. La pérdida de su papel dominante como heraldo intelectual del arte, ha dejado libre y aligerada de sus responsabilidades históricas a la pintura y ahora, con una pintura situada junto a la poesía en un arrabal de la historia, podemos regresar a la obra individual sin necesidad de una justificación ideológica. Para decirlo en términos de escuela: como producción posthistórica. Desde esta perspectiva se divisa adecuadamente la obra de Vilà, quien, por singular habilidad, elegió la vía italiana cuando dominaba la francesa y americana. El tiempo no es el mismo en espacios distintos y los espacios de Vilà gozan ahora de un tiempo estable, al márgen de las tempestades postmodernas, y posee una actualidad que sólo es suya.

Desde aquellos paisajes urbanos que continuaban la exploración de los metafísicos italianos por una vía más áspera, ahora Vilà se desplaza hacia el paisaje tout court, a una naturaleza pensada como un organismo viviente, para tratar de habitarlo con ese modo peculiar del pensamiento que es la luz.

Sin embargo, se observará que los espacios vivos van acompañados de naturalezas muertas y que las naturalezas muertas de Vilà son escenas saturadas de claridad, de coloración matinal resplandeciente, lo que contrasta decididamente con sus paisajes de luz crepuscular y dramática, ausentes de toda vida, construidos entre dos luces para que ningún contraste pueda dar lugar a una línea. La luminosa viveza de los objetos inanimados y la agonía mortecina de la naturaleza viviente establece una oposición de la que los humanos parecemos excluidos. No hay ni una sola figura en la pintura de Vilà. Y se trata de una ausencia tanto más destacada cuanto que en todos y cada uno de los paisajes y naturalezas muertas está presente el trabajo humano. Vemos la obra, pero no el cuerpo. Vemos huellas, pero no la mano. Ésta es, por lo tanto, una extraña manera de habitar el espacio

Si no me equivoco,todas las pinturas de la exposición proponen huellas conspicuas en primer plano (carreteras, escaleras, chimeneas, muros, postes o embarcaciones), excepto una en donde los troncos constructivos aparecen tachados por un árbol caído (o en trance de caer) cuya diagonal atraviesa la escena con la violencia de una condena. Hay una voluntad negadora muy presente en estas naturalezas vivientes, deshabitadas, y marcadas con las cicatrices del trabajo humano. Los caminos de estos paisajes no conducen a ningún lugar, pero en un sentido totalmente distinto a los holzwege de Heidegger, porque aquí no cabe ni siquiera la posibilidad de perderse.

Ninguno de estos caminos nos permite, rigurosamente, salir de donde ya estamos. Si los siguiéramos entraríamos en una de esas pesadillas de disco rallado en las que siempre se regresa al principio o se sale a la entrada. Así la fuerza cinética de la pincelada, siempre espontánea y de primer toque, queda detenida o congelada por la espacialidad inmóbil.

En la pintura última de Vilà ha desaparecido la memoria de Carrá y Sironi que conservaba en sus anteriores pinturas de ámbito ciudadano. Aquellas perspectivas industriales, cuya soledad se veía subrayada por un cromatismo agresivo, ha fluido hacia estos restos de la vida urbana semejantes a ruinas que se insinúan en los nuevos paisajes, produciendo un efecto aún mayor de desolación, un efecto más intenso de alejamiento y condena. Cuando la última huella urbana desaparece en ese único paisaje sin memoria humana, entonces la caída de un árbol tacha el paisaje con un trazo inapelable. La naturaleza parece anularse a sí misma como un ámbito sin salida. Decir que estos paisajes de Vilà son naturalezas muertas, no es un mero gusto por la paradoja.

Por el contrario, la vivaz luminosidad de las granadas, los ecos cromáticos de las cajetillas de cigarros, las tijeras o los naipes (aquí continúa fresca la memoria del mejor De Pisis), se muestra a veces contra un paisaje soñado entre objetos mudos y quietos. Sin embargo, el paisaje que se abre en el interior de las naturalezas muertas es un objeto más entre otros objetos, y ofrece su fuga espacial sólo como aceleración compositiva, pero el espectador sabe que el tiempo de estos paisajes no es el de la naturaleza viva sino el de las cosas muertas, es el tiempo sin transcurso del sueño y del poema.

Un iconólogo que se inclinara sobre la simbología fúnebre de las granadas podría pensar que Vilà pinta vanitas con naipes, a la manera barroca. Pero no es el caso; los espacios de estas naturalezas muertas nos permiten echar un vistazo a los paisajes irreales sin necesidad de apoyos externos, ni intelectualismo gráfico. No hay en Vilà la menor intención moralizante. ¡Todo lo contrario! Precisamente por eso las naturalezas muertas de Vilà son verdaderos paisajes y no ilustraciones de una lección moral. Y de ese modo se arrancan a la muerte.

Si la obra de Vilà ha estado siempre traspasada por el lirismo (no es casual que numerosos escritores coleccionen sus pinturas) en estas piezas ha renunciado a una última colaboración con la prosa que todavía formaba parte de su obra anterior como incitación imaginativa, aunque quizás vuelva a aparecer en su obra futura. Por ahora, la depuración pictórica de Vilà es absoluta y su propia radicalidad (poco perceptible para quienes están habituados a radicalidades de espectáculo) anuncia transformaciones inmediatas. Las dos pasiones artísticamente incorrectas de Vilà, el individualismo y la amoralidad, están produciendo signos de orientación en sus espacios inhumanos. Quienes conocemos su trabajo desde hace años, comprobamos que su última obra, siendo su pintura más desnuda de toda insinuación de vida, es también la que propone un horizonte más esperanzado.

Félix de Azúa

Jordi Gabarró

A menudo pienso que la pintura ya ha llegado a su fin y que este fin de trayecto es un cul-de-sac; que en este arte ya se ha hecho todo lo que se podía hacer.

El nuestro es un siglo de grandes mentiras: mentiras políticas, mentiras sociales, mentiras artísticas. Durante generaciones hemos dormido en el sueño del engaño. Y lo que es peor: probablemente nos lo hemos merecido.

Ante esta realidad, la pintura, el arte de pintar, los he visto como un absurdo anacrónico: la constatación de su absoluta decadencia. Nuestros hijos, nuestros nietos, los niños de los ordenadores, de la realidad virtual, ¿pueden realmente sentir algún interés por las imágenes anticuadas, humildes, discretas, de un "simple" cuadro pintado al óleo?

En la misma medida que el cine hoy en día está sustituyendo posiblemente buena parte de la literatura, especialmente la novela, también es probable que el centelleo de las pantallas de los ordenadores acabe tomando el relevo del antiguo arte de pintar.

Este futuro próximo que se percibe cierto no nos despierta ningún optimismo, ningún entusiamo. El progreso, medido únicamente mediante los avances de la técnica, es una broma irónica d elos dioses.

Sin embargo, el instinto de supervivencia de la parte más noble del espírituhumano, en su desesperación, es violento y profundo. El alma no se resigna fácilmente a renunciar a sus prerrogativas, a sus capacidades. En la naturaleza, -este caos ordenado-, se produce un contrasentido hiriente: mientras la pintura agoniza tocada de muerte, nacen en el mundo absurdamente nuevos grandes pintores.

Los tiempos no les son propicios pero una vocación irrenunciable les empuja a pintar.

Y es en el espacio obsesivo de su voluntad donde se produce el milagro: el camino que veíamos sin salida, agotado, consumido, no ha dicho todavía su última palabra. Prosigue, continúa atravesando parajes nuevos desconocidos. La defunción que preveíamos próxima queda momentáneamente aplazada.

Miquel Vilá, el artista, simboliza perfectamente esta lucha de los grandes pintores actuales contra la muerte de la pintura.

No es fácil hablar del universo pictórico de Miquel Vilá. En primer lugar y esencialmente, se trata de una lucha constante contra el estado agónico de su arte. Ha visto el engaño de las últimas décadas, prostituidas y ridículas, manipuladas por los marchantes internacionales. La conciencia del gran fraude le inflama los pinceles de un fuego violento y airado que no todos los espectadores pueden soportar. No cabe duda que su pintura no es apta para pusilánimes.

Los paisajes, las ciudades, los objetos, especialmente estos últimos, son maltratados a conciencia con una pincelada que en apariencia los asalta y los descompone pero que, en el fondo, los comprende. Detrás de la aparente destrucción existe un acto de creación.

Vilá, que ha entendido a los grandes maestros, como es posible pintar hoy, como lo harían éllos si hubieran nacido en nuestra época. La fuerza de estas desoladas imágenes nacen de la desesperación y del orgullo de quien se sabe solidario y epígono. Y seguramente, de este estado de vigilia, de desesperación, es de donde surge el secreto aliento poético que se oculta detrás de la hiriente realidad de sus cuadros. El pintor sabe perfectamente que la reproducción mimética de esta realidad no tiene ningún interés: sólo en el misterio, en el enigma, se hace evidente la potencia del talento. La obra de Miquel Vilá, -que ha sufrido una progresión vertiginosa-, constituye un desafio a los principios establecidos, a la dictadura de las modas, al desierto cultural que nos rodea, a nuestra hipocresía cobarde, a tanto falso progresismo, a la auto satisfacción cotidiana, a la nada.

Quizá por todas estas razones su obra puede resultar incómoda, agresiva, agreste, tosca, hasta incluso indecente como un exabrupto. No todo el mundo sabrá ver en élla el sustrato de ingenuidad i de delicadeza tan púdicamente disimulados. La relación del pintor con su obra y con el público que la puede contemplar es un estado de lucha permanente, de combate, de vibración obsesiva. Pero también es al mismo tiempo una relación de comunicación, de esperanza, de amor.

Creo que en su grito, en este centelleo ardiente y torturado de los colores, es donde se hace posible que el camino del que he hablado antes persista y no se detenga. Tenemos que agradecerle a Miquel Vilá este pequeño milagro.

No se si este hecho tiene alguna importancia o simplemente es anecdótico, ¿qué son las obras de los hombres? pero en cualquier caso pienso que da sentido a una exposición.

Jordi Gabarró

REVIEWS

Alex Susanna

On the occasion of its seventy-fifth anniversary, Sala Pares hosts a large retrospective exhibition by Miquel Vila, one of the most unique Catalan artists of the last forty years. But what do we mean by singular? Someone endowed with a strong personality, someone who at all times has fostered optimal growth of his work, and someone endowed with great faith in his craft. Personality, growth, faith. But perhaps above all Miquel Vila has been someone able to create his own imaginary, therefoe we are already talking about talent.

Holding an incorruptible and persevering talent, as shown by the exhibition we present, which summarizes a trajectory of almost half a century: from some of those first works -between surreal and indebted to pop art- which he exhibited in 1968 at the Ianua (Barcelona) or Pecanins (Mexico) galleries, or in 1969 at L'Agrifoglio (Milan) and The Mande Kerns Center (Eugene, Oregon), to paintings painted in recent years at his study in Barcelona or Menorca, in which his work seems to have reached an extreme degree of condensation. Minimal still lives, landscapes without anecdote: pure plastic.

It is therefore an exhibition that both the artist and Sala Pares -his gallery since 1990- owed us, so that the first thing we must do is to celebrate it properly. It is not yet the great retrospective that Miquel Vila deserves, but perhaps it is the preamble. And, at any rate, the choice of these sixty works becomes not only a real compendium of motifs and genres but as an excellent gateway to their world. If you wish, it is an infrequent exhibition format — like the equivalent of a poetic anthology — but very useful and suggestive for bringing the work of our modern classics closer to new generations and giving others the opportunity to take an express trip throughout his career.

The work of Miquel Vila is, in appearance, the one from an outsider, from someone who seems to have moved along the gutters of the main currents of art of our time. But if you look closely, it's not even close to what it seems: if there is a cultured painter, traveled and read, that’s him. A painter, moreover, endowed with a high degree of self-awareness. The grace of it all is that this has made him extremely independent: as is often the case in these cases, he has chosen his predecessors - the affinities that for some reason are called elective - and has never stopped talking to them. Instead of the much more crowded French or American routes, he has preferred to travel mainly through Italy and is therefore with some of the leading painters of the twentieth century who, since the mid-seventies, he has talked to more , when his work finds its own tone : Carrà, Sironi or De Pisis, to name just a few. However, they are not the only ones.

Therefore, contrary to what it may look like, we must not see Vila's work as the more or less melancholy expression of a soliloquy but quite the opposite. Earlier we mentioned some Italian painters but now it's time to add his own peers: Josep Vives Campomar, Xavier Serra de Rivera and Francesc Artigau are perhaps those with whom he has sustained a more fertile relationship. And, as a matter of fact, this has produced many joint exhibitions. All of them are part of the so-called generation of the 60s, one (by the way) of the most invisible at our public museums.

Be that as it may, you recognize his paintings -almost always- immediately: there is usually a "Vila’s atmosphere", as Francesc Fontbona said in the prologue to our artist's Reasoned Catalog (2004), which emerges in every piece of work and ends to set up a world on his own. A world made of both external and internal references: apparently we find the same motifs or pre-texts, but more than their visible and recognizable materiality what it matters to us is the point of view from which they are observed, or rather presented.

A perspective that is always very subjective and fruitful, often disturbing and all: the physicality of its landscapes -industrial or natural- usually crystallizes in a world of a certain unreality, in the same way as the objects that inhabit its still lives are almost always - out of place - but that's why they create completely unexpected magnetic fields. The subversion of the real, here is the motto that implicitly presides over much of his work.

Now, where does this light comes from that someone did not hesitate to relate to that of Nonell? A dramatic light, autumn evening. An inner light, unctuous, oily, that seems to drip through the skin of objects, or of the landscapes themselves. A fluorescent, end-of-cycle light. That underlines, sotto voce, the loneliness of things and the distance from the landscapes around us, both the industrial ones -already gone- and the natural ones, to which it has more and more appeal. A light that is probably the greatest conquest of the artist and at the same time a sign of his unequivocal loneliness. And, as Jordi Gabarró said, "Miquel Vila perfectly symbolizes this struggle of today's great painters against the death of Painting".

Alex SUSANNA

Rafael Santos Torroella

I watched closely the beginning of Vilà's career. At that time he was fully committed to what it seemed to be his true vocation: etching. At that time when he worked with Torralba, another well known etcher, I even helped in the creation of some of the magnificent books edited by them.

Later, with this sort of shy and silent attitude so common in him, he started to become known for what he was really after: to become a painter. By that time a whole generation from Barcelona, sometimes referred as the generation of the 60s, were hurrying up to get a prominent place: Artigau, Arranz Bravo, Bartolozzi, Llimós, Gerard Sala, Serra de Rivera, just to mention a few. With the latter, outstanding etcher as well, Vilà would share certain affinity to Magritte, a sort of detour which both made to get to what they probably felt it was their most desired aim: a realism with no constraints. A realism that would be true in his natural presence and, at the same time, it would be a recreation or an answer from Painting to Itself.

Afterwards, I saw him advancing lonely, slowly, and stubbornly. At times with some difficulties, but feeling more and more, from his obstinacy, justified by his determination to do it.

Every time I have revisited his work again, at times after long time gaps, I was surprised to find out in his paintings something new, new here meaning different, and I saw him closer to his final goal. Whatever this one would be, it was more a sort of presentiment rather than a clean sketch before his eyes.

However, several years ago, in the mid-eighties, I started to notice in his work, here and there, an unequivocal sudden shine that forced me to restate the same question once again: How does it come that Isidre Nonell, to me the most profound painter that Catalonia has had in modern days, remains with the shining trace of his footprints stopped in time as a glare in the shadows?

I hope that Vilà don't consider me to be impertinent or frivolous if I ask the above question with regard to his paintings. Surely enough, that should not distract him. Yet, I would be way off if I tried to assign to him any kind of mimetic style. Everybody chooses or meets his best friends. And I am pretty sure that among those who were named by Goethe as the 'selective affinities' Vilà would include Nonell and many others. For instance, I listened to him talking about Corot. This, in my opinion, is very consistent with his Nonell's affinities. Perhaps with the latter it is sort of personal and intimate, as it would be arising from his own personal environment.

When talking about Nonell it is absolutely mandatory to mention Francesc Pujols from whom we owe the most fresh and alive views about him. He claims that what Nonell did was to get straight to the essence of beauty, which in the irreplaceable thinker of 'The Tower of the Hours' was a synonymous of life in the fullness of its ripe: "getting rid of everything that makes what classicism is all about, in order to extract from the minimum amount of it, the maximum primordial amount from its substance. If that is feasible. In order that, eventually, the work of art becomes pure essence, as if we would squeezing beauty again and again to bleed it dry."

When looking at the last three Vila's Menorca campaigns, the names of Pujols and Nonell come to my mind again. I see in those exhibitions something described so graphically by the former and savored in such an intense way in the latter. I can see this either in the gravity and the absorbed withdrawal of his Gipsies, as I do in his still life works which are pure and medullary pictorial essence. In the sense that Pujols is using that expression. Thus, we quickly notice that something is going on with Vilà's colors. They are true colors, strong colors, but not only in the shade of their inks or pigments but also because of that value about which the philosopher from Martorell enjoys talking about. These are therefore, vital, substantive colors, that do exist by themselves, towards the inside rather than towards the outside. They don't remain merely on their surface, which is often the case with those painters usually labeled as 'colorist'. If anybody would be surprised by the color density of our painter, being him so much opposed to any superficial inconstancy, he could quote the old Rembrandt when he said to a certain customer who was raising objections of that sort to one of his latest works: "Sorry sir, I am a painter, not a dyer".

This is where the corporeality of things in Vilà's still life paintings comes from. Rather than coming from the shapes themselves it is due to the colors' specific weight. In a similar fashion, you can notice the same in the warm fleshy flowers and vegetables. Also in the shiny crab's shelf or in a herring. Cadmium oxide and ocher amongst metallic green and blue so close to Nonell's. You can see that even on a tiny marina like "El dique flotante, Barcelona" (The floating dock). You can notice on that painting how this substantiveness I mentioned before reaches the water itself, giving to it a beating, a sort of inner animation, blended with its paradoxical still imminence of wave moving towards the beach.

Generally speaking, in Vilà's still life works things tend, like in Nonell's, to be on their own. This is contradictory with the tendency towards piling up, so characteristic of human utilitarianism. In this way, they become protagonist even to themselves which eventually provides them bigger significance. This means that Vilà adds to them a bit of sublimeness but also a bit of pain: they will never assume easily this condition of passivity, this dying motionless serenity which is the last extremity of life.

They remain there, separated but not "standing still". Yet they are active, covered by subtle strains that, as with happens to any other live being, they could be named as intimate. A composition named "Tray and chair in an interior", perhaps is the most finished of the latest Vilà's works I know. In that painting items appear as characters. Everyone is playing his role in the scenography.

On top of that, space plays a role in our painter, either in his interiors or in his landscapes. That becomes an extra element, a very significant one, of the surprising animation, at times even showing a larvating drama, which characterizes his recent work. This space is confined often in his paintings by planes which don't have the usual horizontality or verticality but which imply something different: an inexplicable anxiety, also in an imminence state towards a mystery in front of whose doors we are abandoned, rather captivated than hesitant. It's not uncommon that , somehow as in Nonell, floors attain a relevance in the ambiance of his latest work bigger that the atmosphere and the air themselves. In a way, it's like he would not conspire against them but with them. To direct them in a much better fashion towards this repeated substantiality that, as the ancient primitives (from whom they learnt so much the modern primitives since Cèzanne) knew well, air and atmosphere are always ready to steal.

Rafael Santos Torroella

Francesc Fontbona

Miquel Vilà has consolidated his presence on the contemporary Catalan painting scene. The nearly one thousand five hundred paintings included in the present catalogue of his work objectively attest to Vilà’s considerable weight. But one thousand, five hundred, though it is a lot, is just a number and art cannot be evaluated quantitatively, though a significant number of pieces always serves to emphasize, if nothing more, the magnitude of an artist dedication and the density of a professional career.

Everyone is conditioned by the times, but the painter Miquel Vilà belongs to a generation particularly marked by its time period, a complex and uncertain one which -let’s not forget- has not yet been brought to the sort of close that would allow it to be viewed as something complete.

Vilà is one of the painters appearing on the Catalan art scene from the very beginning -even slightly earlier- of the decade of the 60s, precisely shortly after several Catalan artists of the previous generation had achieved resounding and, until then, unprecedented international success, that of the painters forming the group “Dau al Set”, who had ended up embracing Informalism. Therefore, when Miquel Vilà and his colleagues, at the time very young began painting, many people considered that nothing could be done in art -and even worse- with the dogmatism prevailing at the time, that nothing should be done- other than Informalism, a movement which continued to produce international recognition for Catalan art while the young newcomers tried almost heroically to do different things.

Informalism at the time was the unexpected trump card of new art in this country, and in addition, for us it had undeniably positive political connotations that made it specially valuable. Indeed, it was like a sort of strictly pictorial yet nearly explicit manifesto against the Franco regime that had been monopolizing and oppressing the country for some twenty years. It mattered little that the very same non-conformist art was used repeatedly by the dictatorship to wash his image internationally by officially supplying this type of works to international art biennials, and that the artists creating it were not very diligent in disassociating themselves from the operation. Despite all this, Informalism had become a dogma of progress, and it is well known that dogmas are indisputable and only admit assent.

But the fact is that Miquel Vilà and some of his young colleagues ignored the dogma and dared to seek their own, different solutions when they embarked on their personal creative careers. Nor did they ever consider ending up within any of the traditional pictorial trends, absolutely valid in their own right and in many cases still quite alive but that, from what they were concerned, had already expressed everything they could express. So they move on, into another direction. That was indeed a problematic decision, as beyond Informalism it seemed there was no possible “salvation”. Furthermore, the maîtres-à-penser (I’ve always asked myself why people with a functional brain would ever need anyone to tell them what to think) were prophets of a religion that, like every religion, did not admit heterodoxies. And on the political front, it was also endorsed, because it was perceived as the ultimate line of the international avant-garde at the time.

That daring move towards real heterodoxy was something Miquel Vilà paid for, and continues to pay for, even forty years later since, in not aligning himself with the prevailing forces at the time, he came to occupy the uncomfortable position of “independent”. And independent he continues to be, many years later, for having dared not to place his bets on the winning horse at the right time.

But the fact is that, while in this country there seemed to be no real salvation beyond Informalism, in Europe and the rest of the Western World, there was much more variety of artistic possibilities, even from positions at the extreme avant-garde. Here, there was an intense dispute between the advocates of figurative and abstract art, in which everyone acted in an extreme fashion: the artists coming from the consolidated pre-war tendencies were for the most part irritated by the young advocates of “abstraction”. However, the painters who represented the latter, instead of at least defending the validity of any avant-garde creation, only emphasized the non-figurative aspect, as if this factor was essential for and exclusive of artistic renewal; and many of them seem to ignore or underestimate, for example, the fact that perhaps the strongest of any new painters arriving to the international scene, Francis Bacon, was precisely a figurative artist who used conventional pigments to express himself in his creations.

When the mainstream demanded one thing, Miquel Vilà and a handful of other artists in his milieu had no problem doing other things. And it must be said that it was truly difficult to dissent in those times, in any case, a price had to be paid for doing so. It is always safer to travel in the company of those who have a papal bull than to travel alone or with others who are as disparate as yourself.

From a very early stage, Miquel Vilà was assured that he wanted to take up painting. And painting is practiced with pigments that were invented many centuries ago and have the advantage that they respond materially much better than other, rather poor substitutes that condemn the paintings made with them to visit the restores workshop after a few years to arrest their inexorable deterioration.

Vilà knew from start that, in order to narrate things in color on a flat movable surface, such as oil on canvas -or on panel or cardboard- provided unsurpassed performance. Therefore, as he didn’t need to re-invent the wheel, he was able to dedicate his genius to creative matters.

Another thing that Miquel Vilà was assured from scratch was that, since Maurice Denis time, the subject of the painting had been relegated to the background in order to grant the leading role to the painting itself, to its pure and simple plastic values, he did not want to relinquish the evocative and therefore expressive effects that objects, places, and specific situations have as nuclear elements in the poetry of a piece of art.

Miquel Vilà studied at the Conservatori de les Arts del Llibre (Conservatory of the Arts of the Book) and at the Escola Superior de Belles Arts (Fine Arts School), both in Barcelona, and began his artistic career with several paintings created between 1959 and 1961. None of these earliest works were commonplace, nor did they participate in any of the established languages of the acclaimed avant-gardes.

Soon though, he moved from painting to concentrate on printmaking. Engraving is an intrinsic part of Miquel Vilà’s artist creation -he has always worked with it and on his early period, until 1968, it was nearly his only activity.

Vilà defined his mature pictorial style around 1974. Before, he was searching, following a path not far from the one he would eventually took, yet more receptive to far-off Surrealist influences and nearby pop art stimuli. From the start, Rafael Santos Torroella, an art critic and great intellectual, yet whose carisma as an arbiter of criticism was not recognized -probably due to certain contemporazing postures he held in the political field- backed Miquel Vilà and his colleagues -students of Santos in Fine Arts- who were neither happy with becoming the epigones of Informalism once it had become the official line. The fact that Vilà exhibited at new independent galleries, away from any established movements, such as Ianua and particularly Sala Adrià in Barcelona, is also a significant factor that helps to define the profile of the emerging artist.

Some sentences by Santos appearing at newspaper “El Noticiero Universal” in October 1971, describe the essence of Miquel Vilà’s artwork at the time: “It is a Surrealism that should be quantified as magical, filled with more or less geometrazing and esoteric signs, and always imbued with a grave and melancholic atmosphere suggestive of of oneiric realms, possibly with disturbing childhood nostalgias”. If we remove the references to Surrealism, this portrait of Miquel Vilà’s artwork can be applied to all of his subsequent mature works.

From 1974, Vilà’s painting became increasingly purified, focusing on the essential, which does not at all mean that it became schematic or simplified. There was an evident will to eliminate elements that perhaps were more exterior than intimate, owing more to trends than to “inspirations”. And for a painter who does not want to dispense with these evocative effects of objects and places which I mentioned above, what this purification does is making precisely these “figurative” elements emerge unconsciously, elements which he is never tempted to describe in a naturalist manner, rather translating their forms always to produce a sort of archaic air.

Miquel Vilà belongs to a rare category within Contemporary Art, an unlabeled category which hinders the taxonomy that seems facilitate the job of an art analyst while, at the same time, places its members -as diverse in time and style as Regoyos, Pidelaserra, Feliu Elias, Ottone Rossi or De Pisis- in an unstable, creaking classification, never acclaimed by the administrators of plastic orthodoxy. They could be called the “unsettling authentic painters”, and this category would include those painters who, acting from the most profound depths of creative sincerity, refused, since the end of the 19th Century and throughout the 20th Century, to join consolidated movements or incorporate mechanisms of refinement that could erode the strong, unusual and primal expressiveness of their works.

The anti-naturalist and yet figurative Vilà’s art style has another surprising characteristic: the light. It is very obvious that the painter does not pretend to trap the viewer with illusionism but, at the same time, he refuses to relinquish the above stated well-recognizable references, which he bathes in a special light obtained through techniques that other painters reserve for results at the service of superficial fidelities but that, in his case, serve a symbolic or expressionist attempt rather than an a one into Realism.

Thanks to this light, Vilà make us to believe that many of these industrious and even dismal places filling his canvases are painted at dawn, when in fact, they are products created in the mind, in the solitude of the studio, who knows whether as a result of that disturbing childhood nostalgia that Santos Torroella detected so early in his work, that only use “realist” resources to play with the viewer in a game that the latter can only intuit.

It is in this game that Miquel Vilà’s art resides: Trying to explain it, if this was possible -I have stated before that painters are better explained through the brush and not the word-, would be a betrayal to him. It would be like disemboweling his art, an act not only unnecessary but one of poor taste.

The important thing is that his work will remain, a silent witness of a time that was richer than school books say. And perhaps, volumes such as this one will help to rewrite the art history of the 20th Century such that it is more in keeping with reality, which is what all serious history should aim at.

Francesc Fontbona

s

s